PSA: Despite me spending not nearly enough time talking about that incredible finale, there ARE spoilers for Severance season two in here…

If you ask me, the best plot twist in Apple TV’s Severance came in the early episodes of season two, when we find out that the little white beat-up Volkswagen we saw Patricia Arquette’s Harmony Cobel (or Mrs. Selvig, depending on who’s asking) drive in season one isn’t just a part of the ruse she keeps up to spy on her severed subject Mark (Adam Scott). It’s actually just her car.

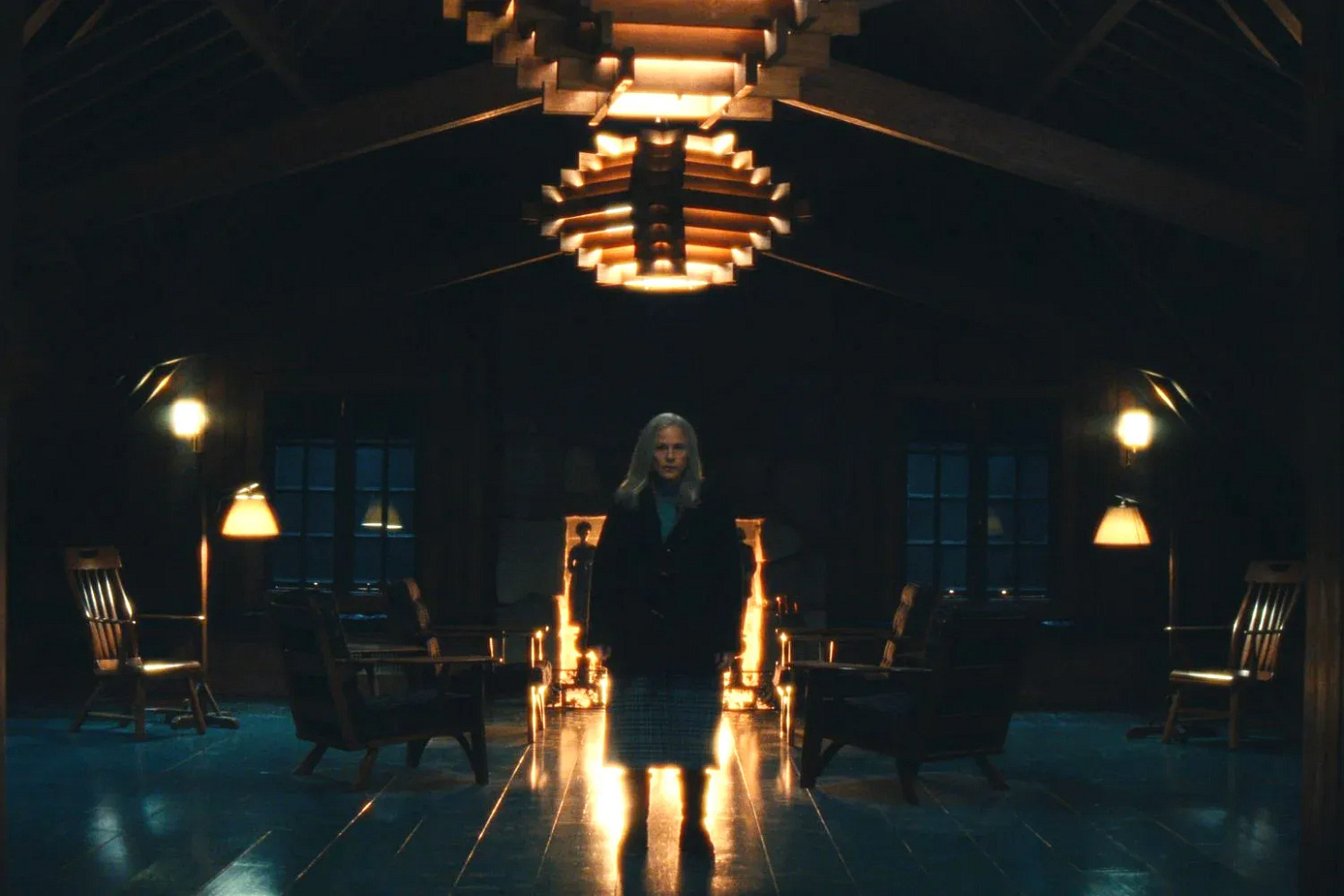

Season one Cobel loomed large as the big boss (read: Big Bad) on the “severed floor” of Lumon Industries, a life sciences (?) company with a mysterious cult-like presence over the town of Kier, which is named after the company’s founder Kier Egan. With her silver hair, power suits and Arquette’s signature brooding glare, Cobel was intimidating and powerful. And so it seemed like an easy assumption that the humble belongings of her alter-ego Mrs. Selvig, Mark Scout’s neighbor and a retired sandwich-shop owner, were all a front in order to gather information about Mark, who in grieving his dead wife opted to get the severance procedure, separating his memories and experiences from work. Selvig’s small company-owned condo, barely-furnished sans a concerning shrine to Kier, seemed as if it couldn’t belong to the real Cobel. Certainly the high-ranking Lumon manager, who is wont to throw mugs at her employees, would have a more lux, sprawling cabin somewhere tucked away in the eternally-snow-covered hills of Kier.

But season two clarifies that Cobel’s life and Mrs. Selvig’s life are more or less the same. There was no fruit born from her labor, no spoils. When she’s ultimately let go from the company she’d dedicated her whole life to, all she’s left with is that old white hatchback.

Severance, at its best, is a show about work and how it weighs on the soul. “Outies” (Lumon employees when they are not at work) lead mostly miserable lives, and “innies” (Lumon employees while they are working, who are essentially entirely different people) are eternally doomed to a life of labor. Innies are slaves. They don’t see the benefit of their paycheck. They don’t get to have families, to see the sky or even to experience sleep.

The show tells us why most1 of Lumon’s severed employees would choose to do something like this to their brain. Mark wanted to escape the grief of his wife. Dylan needed a wiped consciousness, devoid of his listless depression, in order to keep a job and support his family. Helena, as a Lumon heir, aimed to show the world that severance was safe and normal.

Lumon publicly touts severance’s advantages to the employee, like the most extreme interpretation of work-life balance. But what’s unspoken is the advantage of severance to a company like Lumon. It is immensely valuable for employees to forget what happened to them at work as soon as they leave the building. That’s a workforce that, presumably, can’t organize. Can’t whistleblow. Can’t even quit without permission from their outie. Severance creates a captive and silent workforce, something that would pay off in spades for someone like Jeff Bezos.

Of course, Lumon is doing something even more nefarious, which has been the central mystery of this season. All the work Mark and his colleagues do is encrypted. Different departments on the severed floor are actively kept from each other. As we go further down the rabbit hole, we find Lumon is even more shady and despicable than it seems. And even after an action packed finale this week, we’re still left with more questions than answers.

It's fun to theorize about whether Ricken is a secret spy (or a goat). And it’s been shocking to discover that Mark’s wife is actually alive and trapped on the bottom floor of Lumon, her brain split into two dozen innies all being tortured daily. But although the complicated love triangles between innies and outies, the push and pull between Mark S. and Mark Scout and the ScFi depths of Lumon’s lore have all made for good TV, Severance is at its best when it keeps it simple, when it’s a show that has a lot to say about work.

In season two, we find out that Cobel was raised in the cult of Lumon. She was a child laborer, working in the ether mill and huffing fumes at eight years old. Her intellect was deemed promising and so she was offered a chance to rise up the ranks, entering “the Wintertide fellowship,” which eventually propelled her into her role running the severed floor.

But Cobel was more than just a dedicated administrative servant, she was a woman in STEM! She invented the severance procedure, the original designs scribbled in a notebook stored in the cellar of her childhood home. Of course no one knows this. The current Lumon CEO and oldest living Egan, Jame, took full credit for developing the procedure, but gave Cobel the privilege of overseeing the products of her creation, the monsters to Cobel’s Frankenstein.

This bombshell informs much of the tempered rage that we see bubbling up in Cobel in season one. Lumon’s never-present-but-always-watching Board of Directors won’t even deign to speak with her despite her invention continuing to pad their pockets. But she directs her ire down, taking a vindictive delight in torturing her severed subjects. She plays mind games with Mark (he asks if she wants the door to her office opened or closed and she hilariously glowers at him, “both”) and has no qualms with drilling a hole into Petey’s corpse while his family is grieving a room away.

But that Cobel is the inventor of severance also says a lot about the procedure itself. Although it’s a bad boss’ dream and a union organizer’s nightmare, severance wasn’t invented by a company-side employment lawyer at Jackson Lewis. It wasn’t born from the imagination of a greedy corporate CFO. It came from a child who from birth had a life revolving around work. Difficult, exhausting, unrelenting work.

Severance didn’t stem from a corporation hoping to keep a workforce silent, it emerged from the same set of desires that Mark and Dylan had. Work is a cancer eating away at the cells that make up the rest of our life, which as a result, isn’t really ours. We’re just leasing space in a building owned by someone else and the rent is too damn high. You try to find meaning in the 40+ hours of your week that belongs to someone else, but sometimes you just can’t. Cobel, at eight years old, couldn’t. Mark, drowning in grief, couldn’t. Dylan, meandering and bored, couldn’t.

So instead, you could imagine a young and beaten down Cobel saying: What if we just didn’t have to? The root of severance, as I imagine it, is a beleaguered understanding that work shouldn’t exist the way we do it. But indoctrinated into a cult of productivity worship, Cobel didn’t have the capacity to imagine a life, a world, entirely without work. The best she could do was an extraction from her consciousness. She came up with a solution that serves the proletariat in the short term without threatening the means of production, that doesn’t disrupt the system but in fact adds to it. It’s not dissimilar to the labor movement emerging, battleworn, from the Industrial Revolution with the prize of a five-day work week, and decades later we still lack the collective imagination, and determination, to dream of more.

So of course Lumon latches on to Cobel’s idea and continues to milk it for all its worth. But the irony is that Cobel, herself, is not severed. Even though as viewers, we don’t see Cobel work her way from a lowly factory worker into a pant-suited girl boss, it’s easy to imagine how the journey, by design, brought her closer to Lumon. Even though it was likely her own grip that kept her from falling, she thanked the ladder, was loyal to the object that gave her the opportunity to climb. She no longer wanted to forget about work, to eradicate it from her psyche. Instead, she, somewhere along the way, found the meaning that was lacking before. She saw the promise in work, the opportunity, and devoted her whole existence to it. When she got to the top, it was clear that the promise was just a mirage. And it wasn’t really the top at all. But even then, while her bitterness was palpable, she remained a loyal servant, with little to no sympathy for the subjugated people she’d inadvertently created based on a longing for freedom.

When Cobel is finally ejected from the ride without her consent, we watch as others happily take her place. The show, in season two, explores a different flavor of the middle management purgatory: (*trigger warning*) DEI. In season one, we saw Mr. Milchick (whose first name is revealed to be “Seth” and something about that just isn’t sitting right with me...) as Cobel’s jovial yet menacing number two. He was the hands-on leader of the group who would facilitate ice breakers, melon parties and “dance experiences” but could also break a refiner into submission Professor Umbridge-style if they acted up. But in season two, we see Milchick’s ambition shine through. He is eager to take over Cobel’s desk, and assure as many people who will listen that he is going to run the severed floor better than she did. But of course antics ensue regardless and viewers can almost feel bad for him as he’s belittled by higher-ups.

As we learn more about Cobel’s journey to the top, it’s easy to imagine that Milchick was cut from the same cloth. We don’t know anything about how he became indoctrinated into the world of Lumon but it’s clear throughout the season that his loyalty runs deep. Even in season one, there’s a moment in “the break room” (think, literal interpretation of a break room) in which Milchick is psychologically torturing Helly R. and she pleads with him “You seem like a nice person, don’t you see how fucked up this is?” But he doesn’t even flinch.

Milchick and Cobel share a lot of the same experiences, but the show makes it clear Milchick is different. Everyone embedded in Lumon speaks in an old-world, stilted kind of cadence. And yet Milchick throughout season two is constantly reprimanded for it. The most emphasized piece of his performance review isn’t the multiple employee uprisings that have happened under his watch, it’s his use of big words. I can’t imagine it’s lost on these Lumon higher-ups that among the company’s core principals are words like “frolic” and “malice.” So their constant nit-picking at Milchick’s phrases like “eradicate childish folly” are a clear effort to let Milchick know he isn’t one of them, not really. This was cemented earlier when, upon his promotion, Milchick was presented with a series of paintings mimicking the ones scattered throughout the severed floor depicting the life and stories of Kier Egan. But Kier’s skin had been darkened, so that Milchick may “see himself reflected in the founder.” The face acting that both Tramell Tillman and Sydney Cole Alexander gave in that scene was top notch, the unspoken understanding2 between both of them that not only was this ridiculous, it was wildly insulting. But they took it both with a pained smile.

We watch as Milchick is pushed to his breaking point the further he climbs the Lumon ladder. We see his decorum break when he tells Drummond to “devour feculence” or eat shit. And he makes an iconic dig at an animatronic (but somehow sentient?) Kier Egan that the model is inches taller than he was in real life. But Milchick never goes far enough to actually leave Lumon or rebel against it. Like Cobel, he mostly directs his frustrations below. He’s at odds in season two with the next generation, the current Wintertide fellow, a couldn’t-be-older-than-14-year-old Mrs. Huang. Milchick should see himself in Huang, an eager-to-please Lumon youth who also checks some diversity boxes for the company (though they might not want to put her on a pamphlet until she turns 18....). But instead he sees her as a threat to his position. While the severed employees look at Huang with concern -- Dylan especially sweetly asking her to blink twice if she needs rescuing -- Milchick treats her like any other colleague, indicating to us as viewers that at least a piece of Milchick’s humanity has been stripped away.

Through Cobel, the show gives us insight into how these tyrant managers got to where they are, but more importantly it shows the thankless nature of the job. Cobel and Milchick aren’t building a life. They don’t have families they’re supporting with these Lumon paychecks. They don’t even have stuff as far as we’re concerned. It’s telling that in the finale, the animatronic Kier tells Mark to “revel now in the fruit of your labors” before letting Milcheck get up there and do his big one with the marching band (and God did Tillman deliver). What is the fruit? A pat on the back from the company? We all know Mark will not actually be “one of the most important people in history.” No one will know his name outside of Lumon walls. Mark knows this too. He and his colleagues have been beaten down enough to call bullshit. But that’s the strange drug of middle management. Even as we can see he’s wounded, Milchick dances with the marching band, he revels in the fruit of Mark’s labor even when Mark won’t.

Severance depicts the grind of middle management like a treadmill that won’t stop until it’s forcibly unplugged. The greater the incline of the treadmill, the faster it churns and there’s no room for the runner to do anything else but try like hell to stay on. It puts blinders on humanity, leaving no room for empathy for others let alone empathy for oneself. Milchick, in one of the best scenes of season two, looks at himself in the mirror and says “grow up, grow up, grow up.” But all Milchick’s striving towards fitting into the Lumon mold gets him is isolation. At the end of the season, we see him use an impressive amount of strength and energy to break out of a bathroom Helly and Dylan locked him in, only to find himself at odds with an entire room of workers who actually discovered their worth, and the power that they have when they stand by one another. Milchick isn’t part of the union. He made his choice.

You’d have to imagine that if Cobel wasn’t flung off the treadmill at the end of the first season, she would be in the same position. Before the last few episodes, the show did nothing to show us that Cobel was sympathetic to the rebel forces against Lumon. And it’s hard to trust that her intentions in helping Mark are pure. But at one point, in the birthing cabin, Cobel says “I care for you, Mark.” And in her twisted way, I really do think she does.

But while I think Severance is spot on in depicting middle management, the tyranny it creates and the tyranny it succumbs to, I’m not sure I know what to do with it. On the one hand, it’s showing us that Milchick and Cobel are really not very different from the innies. Their lives are just as bleak, and they’re just as overworked and underappreciated. But is it good that we feel sympathy for these managers? Does it excuse their behavior? We’re living in a world of Milchicks and Cobels right now. Thousands of people who are laboring and the only real fruit is the work itself, and the work is evil. So what does that make them? Ziwe’s brilliantly written review of “The Zone of Interest” can now be aptly applied to the majority of the people who run our country or have any hand in turning the wheels of fascism: “For every death, his life becomes materially richer. he is seemingly not driven by any ideology but upward mobility and that pursuit has dehumanized the millions of people on the other side of the family’s wall. Success is an illness and reminds me of all the other career men and women ascending up their professional hierarchies for an idyllic garden built on top of a grave.”

Severance’s season two finale finale showed Milchick pummeled by that illness of success and Cobel seemingly becoming free from it. But what’s so interesting to me is the show left out that “idyllic garden,” as if the sickness of upward mobility is so potent it requires no real material incentive. Afterall, Lumon never feels the need to sever its middle managers, confidently betting that they’ll keep going to work each day knowing full well what’s going on. For a show that is weaving an increasingly complex web of relationships (the Mark S., Mark Scout, Gemma, Helly R., Helena love quadrangle just being one), it’s telling that the most simple one - Cobel and Milchick’s allegiance to a job that truly offers them nothing - might be the most difficult to unravel. I’m eager to watch it happen in season three, although I have a sneaking suspicion the ties won’t break the way we’d expect them to.

B Plot

What is the unanswered question you most need answered in Severance season three?

Mallika: When we get Severance season three in approximately 1,000 years if Ben Stiller has anything to say about it, I need a conclusion to the Dylan G./Dylan George/Gretchen love triangle. I know we’re supposed to care about the messy Mark/Mark Scout/Helly R./Gemma love square but I found the tension between Gretchen and the husband she wants versus the husband she has — who are the same person, in a way — to be much more heartbreaking. Plus, I will watch Merritt Wever in anything. And of course, what’s Irving up to????

Rachel: If season three does not OPEN with my baby Irving and Radar on that train to nowhere, no one is ready for the tantrum I am about to throw. I’m sorry, but Mark Scout’s story has all but reached it’s conclusion. Gemma is out of there, thank god. Mark S. bodysnatched him and he had it coming! I kind of have a feeling Jame Egan is gonna let Helly R. body snatch his own daughter that he hates and I will enjoy watching that play out…. And all the love in the world to my Waxahatchee-loving soul mate Adam Scott. You WILL win an Emmy for this season. But it’s time to retire Mark’s POV. TELL ME ABOUT IRVING. Outtie Irving! All we know is he’s suave as fuck and yet has never been loved?? He’s obviously a radical. WHO is he talking to on that payphone? WHAT was he doing at Lumon for eight years before Mark even got there? And most importantly, HOW, in all of my Cohen-brother-watching, am I just discovering that John Turturro is hot? Like shaking-in-my-boots hot? Ben Stiller your Zionist ass is on thin ice, I swear to God you better not let me down next season…

C Plot

Rest in peace to David Steven Cohen, the head writer of Courage the Cowardly Dog. As Cartoon Network put it, “How you've brought to life a scared but courageous little dog reminds us that we can do anything, even if we're afraid.”

Dan Humphrey is entering the Nobody Wants This universe. Well, not really, but wouldn’t it be fun to see Joanne and her sister absolutely destroy him? Penn Badgley is however lending his voice to Kristen Bell's show.

“Jason Isaacs retracts White Lotus penis comments” is…. a headline. Isaacs was really channelling some Lucius Malfoy bitching last week, not too happy with the question of whether the genetalia he flashed on episode four of this season of White Lotus was a prosthetic. He pointedly did not answer the question but complained about a double standard and put Mickey Madison and Margaret Qualley’s names in his mouth for some reason. But the defensiveness started to make more sense when the actors who played his kids Sam Nivola and Sarah Catherine Hook confirmed it was, in fact, a prosthetic and “he was very excited to do it.” Jason!! If you want everyone to think you’re packing, just go the Willem Dafoe route.

Irving is still a bit of a mystery, but there’s a presumption that he has planted himself in the belly of the beast to disrupt whatever is really going on at Lumon.

Though the show smartly shows us that this camaraderie between them can only go so far. When Milchick looks for more assurance from Natalie later in the show, she isn't willing to give it. They both feel they have too much to lose.

This is an excellent read! You articulated what I love about this show so much. Your observation that the severance procedure came from the mind of an overworked, beaten-down employee and not from a shareholder is one I’ll be turning over in my mind. S3 can’t come soon enough!

First of all this was probably my most entertaining read this week. And also such a unique POV on Severance I have not read anywhere else. I feel everyone kind of chose to forget about Cobel and her episode 😅.

I'm honestly waiting to see her and Milchick lead a full on Kier rebellion in season 3. They both seemed like they were reaching their burning point.